In Part 1 of our Galactic Spiral Structure story, we discussed two necessary ingredients that we need to bring together to create our galaxy – a relatively small, but substantial piece of condensed matter (a neutron star or black hole will do) that will form the galactic centre, and an even more substantial amount of hydrogen that will form (most) everything else in the galaxy. As it turns out, the manner in which these two ingredients come together is critical to understanding how a spiral galaxy and its structure actually form. In the end, I will show you how the two ingredients can create a torus, or donut shape to the galaxy.

Triangulum Galaxy

Askar 151phq; AP Mach2 GTO; ASI6200MM, – Baader LRGB and 6.5nm NB CMOS opt. filters

H: (65 x 450s Bin 1, Gain 200); R,G,B: (60,60,56 x 180s, Bin 1, Gain 100); L: (101x150s, Bin 1, Gain 100)

As a headline image for this post, I am showing my backyard image of Messier 33, or more commonly known as the Triangulum Galaxy. In addition to the normal L,R,G, & B filters, hydrogen alpha has been added to highlight in red, the areas under prolific star creation. Light from massive, but short life blue stars gives the outer arms a blue (and forgive me, even magenta) hue. The Triangulum Galaxy is about 3.2 million lightyears (lys) away, about 61,000 lys across, and contains about 40 billion stars – about 1/10th the size of our Milky Way. It is the third largest galaxy in our local group, and it thought to be a small companion galaxy to Andromeda. The galaxy was visited by Star Trek Enterprise D in 2364, facilitated by an entity known as “The Traveler”, otherwise a single one way trip would have taken over 3000 years at maximum warp. (Click on Astrobin for ful res or the image itself for full res. RASC Zenfolio)

Also in Part 1 of the current series, I discussed how a point source of gravity, formed of condensed material, was necessary for containment of any gas cloud – even under Newton’s Shell model of gravity. This is, of course, a “what came first? – the chicken or the egg” sort of argument so I am going to drop it, at least for now – and suppose that sphere of gaseous material (our first ingredient) can exist that happens to come across our second ingredient (in this case I will call a “black hole”) in space. Nonetheless, I believe it is useful to review what happens to a molecular cloud from two points of view. The first is from the standpoint of the individual hydrogen elements (atoms or molecules) in the gas cloud, as from their standpoint the black hole is absolutely massive compared to them. The second point of view is from the gas cloud as a whole, since it is, in its entirety, a much larger mass than the black hole and subject to both its own gravitational field and other inertial forces, as well as that of the black hole.

Along the way, I am going to lean on an interesting paper: C. Alig, A. Burkert, P.H. Johansson, M. Scharmann: “Simulations of direct collisions of gas clouds with the central black hole”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 412, Issue 1, March 2011, Pages 469–486, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17915.x. for help and some figures.

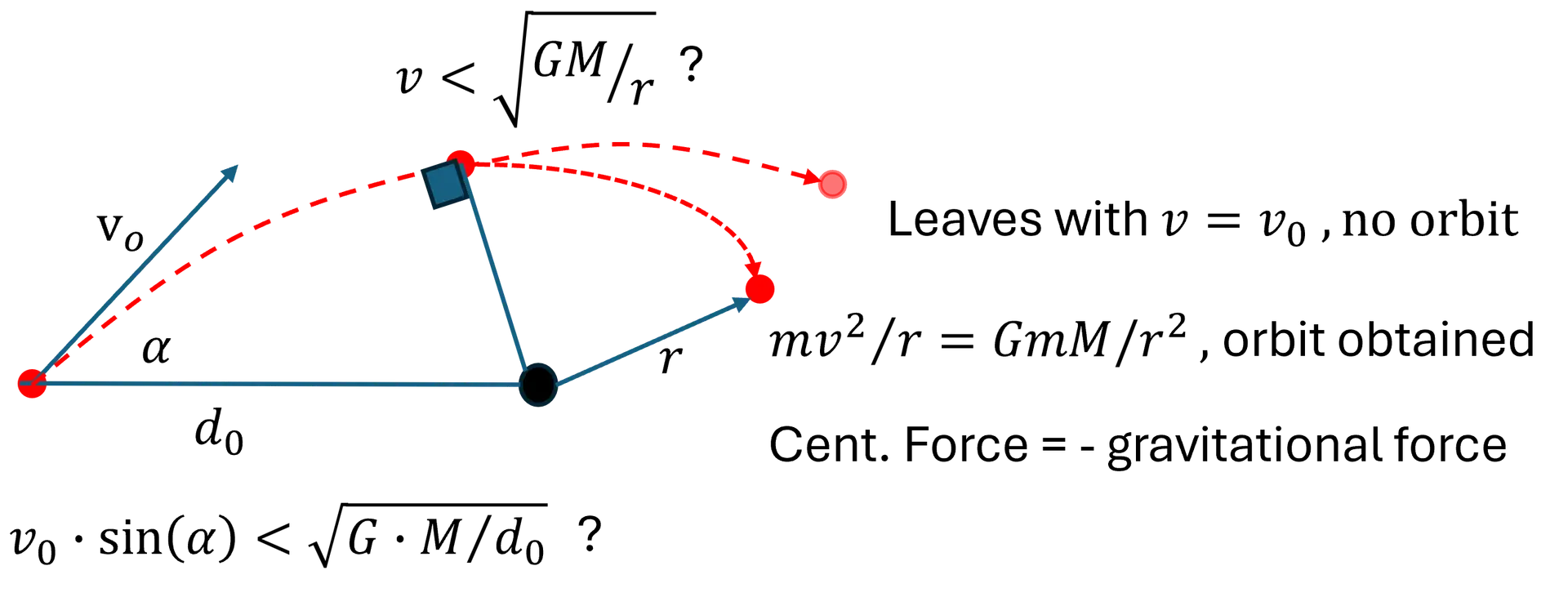

Imagine a hydrogen molecule or atom somewhere within the cloud moving past our black hole. Both the cloud and black hole may be moving, but we will choose the black hole as our static point of reference. For simplicity, at this point, we will assume that the black hole lies outside the radius of the cloud itself so we can avoid any direct collision issues. As our particle/molecule/atom attempts to move past us, it will increasingly be subject to gravitational acceleration towards the black hole – initially on the same trajectory as the cloud as a whole. Part of the gravitational acceleration will be used to increase the velocity of the particle, and part of the acceleration will be used to bend its trajectory towards the black hole as it curves around. Continuing on this now curving path, the particle will reach a point where the path angle becomes perpendicular to the black hole itself. Gravity will be acting like a force pulling the particle towards it the black hole. However, the particle will also experience an apparent “centrifugal force” due to the curved trajectory (radius r) that pulls it away. The amount of centrifugal force is dependent on how fast it is going and if travelling fast enough (called the “escape velocity“), gravity will not be able hold the particle in orbit. The particle will move away from the black hole If travelling slower than the escape velocity, the particle will be captured in orbit around the black hole. It will be these hydrogen particles, that are gravitationally captured in orbit around the black hole that will form our new galaxy.

Just a word about centrifugal force – it is an inertial force that technically isn’t real, because its interpretation depends upon the frame of reference. In another reference frame, the centrifugal force is really just the law of inertia – that without an external force a body will travel in a straight line. In an orbit, gravity is continually acting to bend the particle’s trajectory – in this case, around the black hole. Centrifugal force is how we express the particles inertial desire to keep moving in a line. I would like us all to forget this technicality for the time being, because from our reference point it is indeed real and if you don’t believe me, you can just think of how it works in our life experience. Centrifugal force is used by a centrifuge to separate materials – and this separation is indeed real. You also feel it when you traverse a corner in your car. It is a very useful concept in understanding the structure of galaxies, and indeed Kepler’s laws of motion including the movement of the solar system. The concept will also be referred to as “angular momentum”, which is just another way of saying the same thing. Just a reminder however, is that I have discussed three important forces thus far in the series that we should be keeping in mind, 1) gas pressure – due to the random kinetic energy of gas particles, always trying to expand 2) centrifugal force / angular momentum that, when rotating, creates a force that wants any two masses to move apart, and 3) gravity of course that is doing its best to prevent either.

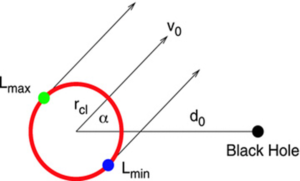

The next thing that I would like to consider is that is more likely that a spherical nest or group of particles might arrive near our black hole at the same time – even though, just for now, we can assume that all these particles are independent acting. We can assume for now, that the distribution of particles is uniform within this sphere and we will make use of the image at right from C. Alig et al , to set up the variable. If we applied the formulas from above to each individual particles we could see how much of the cloud would end up orbiting the black hole, and how much wouldn’t. Or we could perform our math on a hydrogen particle that exists at point Lmin and at Lmax – If v0 at Lmax is below the escape velocity, then all of the material will end up in orbit, if v0 at Lmin is greater than escape velocity, then none of it will. Of course, a third option, than only part of the cloud ends up in orbit can occur. For now, we will be assuming that all of the particles will end up being captured. Ultimately we will want to consider all of the points in the sphere, but we can start with the particles at Lmin and Lmax.

Both particles have technically the same energy and velocity going by the black hole. However, the gravitational attraction of Lmin to the black hole is the greatest and once in orbit, it will also end up with the largest counterbalancing centrifugal force. The end result will be that the Lmin particle will have the shortest orbital radius to the black hole. The opposite will be true for the point at Lmax – it will end up in the largest radius orbit. The points with the planar circle between Lmin and Lmax will end up in orbits between min and max, with an increasing density of particles in the middle. Since all these points from the cloud begin on the same plane as Lmin and Lmax, their orbits will also be on the same plane. However, our original cloud is actually a sphere – there will be an Ltop (infront of the page) and and Lbottom (below the page) on our sphere. These points will also end up orbiting the black hole too! However, their orbits around the black hole will be at an angle to the principle plane. Depending upon the arrival time of the particle, and its initial position in the cloud, the resultant orbit size and plane will vary about a predominant/average rotational plane and orbit size, R. Variations in orbit plane and size is represented by a radius, r about the average (centre of mass) orbit. The net result of all this will be a distribution of particles and orbits that will form a torus or donut shape around the black hole. Now I admit that this is a very simplistic view of how a galaxy forms, but the main takeaway from this article should be that the main structure of a spiral galaxy is that of a rotating torus of hydrogen about a central gravitational attractor, admitting that the actual spiral arms and decorative jewelry of stars and dust have yet to be explained.

I did say that I would repeat this process, with consideration to the fact that the shear amount of gas in the cloud imparts a gravity upon itself, and that the mass of the gas cloud is much larger than the mass of the black hole. Note that in the Milky Way, the black hole represents less than 1% of the total galactic mass. But before I do, I want to thrust a thermodynamic dagger into the heart of Newton’s Shell Theorem, when we pretend that it can stabilize a gas cloud. According to the theorem, the gas sphere should be contained by the external gravity of the outermost shell. Running with this theorem, as the gas cloud approaches a black hole, gravity will pull on the cloud and, at a distance, will create a nipple in the outer shell closest to the black hole. This will cause the spherical symmetry to be broken, and interior gas would leak out like toothpaste out of a pressured tube with the cap taken off. Visually, the results would be impressive, if hydrogen weren’t invisible, as the remainder of the shell suddenly accelerates in the opposite direction like a leaky balloon. Since neither of these things happens, it is far more likely that our gas cloud exists at extremely low pressure, with gravity providing, at best, a sort of weak surface tension like property to the cloud. (It is far more likely that any cloud already has some sort of condensed material at its heart). At any rate, I visualize this as if a metallic wire were being drawn from the cloud and wrapping itself around the black hole in our torus shape. As a visualization of this, I have included a Nasa Goddard video of a black hole dismantling, and then taking on some of the material from a star.

One gigantic difference between the star in the video, and capturing material from a cloud is that the star begins as condensed matter. The gas is expanded from the star before being captured as a torus. For our cloud, the material already exists as a gas, most likely as atomic hydrogen in an ISM. The massive gravitational potential energy of cloud with respect to the black hole is converted to kinetic energy as it ends up orbiting our black hole, but much of this energy also goes into compressing the gas itself. This compression ratio is likely of the order of 1000s of times, resulting in the captured material being 1000s of times the density and pressure of the original cloud. Under such compression ratios, atomic hydrogen will combine with itself to form molecular hydrogen, or H2 molecules, as described in Part 1 of this series. The presence of molecular clouds, in addition to monatomic hydrogen, will be necessary to both describe how spiral arms form as well as needed to create stars.

The ability for such a small black hole to attract such a large mass of hydrogen is subject to the positive feedback of mass transfer. While initially, the gravitational attraction is only due to the mass of black hole, itself – from a distance material added to the torus orbiting it will effectively add to the point source map and grow the amount of attraction – sweeping a vast region of its material and only ceasing when the material is exhausted. The new galaxies’ gravitation field acts as a point attractor from a larger distance, but new arriving material will tend to be added to the outside of the torus. Applied mathematicians, Kevin Brown, on his math pages website, has worked out the integral equations and power series approximations for the gravitational field around a torus, and Niko Nyrhilia, on his Github page, “Niko’s Project Corner” has presented a great visualization of the same.

Axial graviation is always down towards the central plane of the torus. In the radial direction, at radia greater than the ouside radius of the torus, the gravity is towards the centre, while within the inner radius of the torus gravity pulls away from the centre – making for a very interesting saddle condition when the gravity of the black hole is superposed upon that of the torus. Material being added to the torus will depend upon its angular momentum and its plane of orbit, but also the gravitation field it is subject to along the way.

Turning to the original paper by C. Aligg et al, have actually done numerical simulation of the process of colliding a black hole with a molecular cloud. I show here a radial slice through the results of one of their simulations. The arrows represent the circulation path around the central black hole. In these simulations, the colour represents the density of the hydrogen material, and the indications from the simulations are that compression ratios of 5 orders of magnitude are obtained over the original gas alone. As we discussed, these high compression ratios are needed to achieve molecular cloud (MC) formation within the galaxy. You may also note, that you cannot actually see neither the black hole, nor the inner torus ring in this simulation result. I guess we can’t have it all, but I will be discussing the inner torus ring and what goes on very close to the central gravitational attractor in future posts. You may also be seeing some spiral arms in the there, but that would be getting ahead of ourselves also. From the simple process of gas accumulating around a black hole, we have created a complex, non-linear, dynamic system that is starting to look somewhat like a galaxy. I wish I could show you an image of a hydrogen cloud accumulating around a black hole, but as I said in Part 1, hydrogen gas is mainly invisible.

Fortunately, a hydrogen cloud or a star is not the only place a new galaxy can get material from. Gases, along with all of the other galactic jewelry, can be stolen from another galaxy – all they have to do it come to a near collision. There are oodles of examples to show examples from, many of which make up Arp’s catalogue, but one l

cannot resist from showing is The Antennae Galaxies. Original two spiral galaxies with two central massive black holes, minding their own business, they are now locked in a chaotic battle from material – including gases, dust, and stars.

It may appear that I am breaking my promised goal of explaining why spiral disk galaxies are the way they are and that I have deviated from the path by explaining why a galaxy should be in the form of a torus. In the next part, I will finally get to the spiral part. Along the way, I hope to explain why the hydrogen that makes up the galaxy is not an ideal gas because it is subject to friction and viscosity and how that this morphs the galaxy into spirals in it efforts to become as ideal as possible. Once we are there, we can add in all the jewelry manufactured by the galaxy to make it look as pretty as it does in the Triangulum image.