M74 Galaxy in Pisces

Askar 151phq; AP Mach2 GTO; ASI6200MM, – Chroma Broadband and 5nm Ha Filters

L: (111 x 120s, Bin 1, Gain 100); H: (51 x 720s Bin 1, Gain 100); R,G,B: (48,59,61 x 180s, Bin 1, Gain 100)

Total integration time = 22.3 hrs (Oct 6 & -9-12, 2024) Maple Bay, BC, Canada (Click on Zenfolio or Astrobin for full res. image)

This image of the M74 (Messier 74) Spiral Galaxy is often used as the archetypal dual spiral galaxy, and I thought it was appropriate to use as a backdrop to my latest explanation of the structure of spiral galaxies. Those who have followed me in the past, know that I like to post technical and somewhat detailed explanations of what I believe is going on in our astrophotos. Other the the beauty of the images themselves (even though they pale in comparison with others’ posts), it is the challenge of the puzzle that I enjoy the most.

Where I had hoped to leave you with in Part 2 is the view of a compressed molecular hydrogen cloud with the individual molecules orbiting a black hole with individual molecular angular momentum such that the outward centrifugal force on the molecules balancing off the gravitational puling toward the centre. I suggested that the orbits of the particles follow a fundamentally circular (although strictly speaking eliptical are allowed) orbit around the central mass with a mass weighted average orbital distance of big R. Individual particles, of course will vary in their orbital distance (by virtue of their angular momentum) and their axis of orbit. The variation in this orbital distance and axis is represented by a radius of orbits about the mean.

Other than the fact that there are no spiral arms in this model, the main issue with this model is that it continues to treat the gas molecules/atoms as individual acting particles. In order to understand why spiral arms form, we have to recognize that there are emergent properties from the orbiting gas cloud, that compel us to apply the principles of thermodynamics / fluid properties to the cloud itself. As it turns out, internal friction, or fluid viscosity provides a direct answer as to how spiral arms form, and a simple solution to the classic “winding” problem that astrophysicists still grapple with. I will be using the current post to explain this, but on no account should this be considered “ground breaking” news – it may just be an astrophysical blind spot. The second emergent property that needs to be considered is the gravitational field created by the gas field itself, and just as importantly, the superposition of this gravity field with that of the central, condensed attractor. In my next post, I will be using this second “emergent” property of the gas particles to show how the spiral structure is both stabilized and can result in some other observed characteristics of spiral galaxies. This second “self gravity” effect will be dealt with in my next post, but I need to allude to it in the current discussion.

The first fundamental mistake made by astrophysicists is that hydrogen, particularly at the generally low pressures associated with outer space gases is an ideal gas. This is claimed justifiable because the molecules are so far apart from one another – such low density that any intermolecular electromagnetic forces are not significant. However, making this ideal gas assumption is a mistake. No matter how rarefied you make the gas, collisions between gas molecules will occur and it is the nature of these very collisions that is needed to describe how the gas ultimately behaves. The collision of an ideal gas can be considered like the collision of billiard balls, with preservation of momentum and energy, the collision of real molecules, such as H2, is a little more complicated. H2 molecules have a little stickiness to them, or affinity for each other, such that they are held together momentarily, and some of the energy of the collision must be used to tear them apart again. The result is that the final velocity vectors or trajectories will look more alike one another after the collision than they did before. The energy required to pull the molecules apart ends up as heat, such as the net kinetic energy of the pair is somewhat reduced. The effect of the intermolecular electromagnetic force (known as Van der Waal force) is that the directionality and momentum of colliding molecules in brought into conformance.

Let’s apply this to our torus of orbiting molecules. Firstly, any molecules that are orbiting with a slightly off kilter axis/plane of orbit, will already have their orbits warped by the effects of the gravitational acceleration applied to the plane of predominant orbit. This will sooner or later put it in a collision course with another molecule orbiting in a more aligned, or even counter aligned orbit. The result of an idealized collision would be dispersive, but the collision of a real gas will be conformative, even if somewhat mechanically disappative (to heat). That is, both molecules will tend to travel more in line with the average orbital axis/plane and the whole torus galaxy will flatten towards the predominant plane of orbit. If the predominant orbit happens to be eliptical or off-round, the end result of multiple collisions will be to put the whole galaxy out of round. Along will flattening, the hydrogen in our gas cloud becomes further compressed – pretty much ensuring that if our galaxy is big enough, that the hydrogen will be in the form of a molecular cloud. For simplicity, I will now refer to our galaxy as a disc, rather than a torus (although a disc is still a torus in disguise). In the end, it is the combination of the Van der Waal intermolecular attractive forces, guiding the conformance of the molecular orbits and axial gravity the holds the molecules near the mid-plane that counter dispersive effects that will always tend to dissipate the structure.

Before we get ahead of ourselves, I do want to take a slightly different look at our inter-molecular force of real gases. As it turns out, intermolecular attraction is not only at play when molecules collide, it also plays are role when molecules attempt to move past one another. When molecules try and move past each other in a certain direction, their fleeting attraction for one another causes the passing molecules to speed up the molecule being passed. From the perspective of the passed molecule, it slows down the one doing the passing. The direction of relative flow of the molecules is known as a line (or, more properly in 3-D, the plane) of shear, but you can also think of it as the internal friction. If you think of a weight you are trying to drag across the floor, to get it moving you have to apply a force both to give it some momentum and to overcome friction or grip that the weight has to the floor. In an idealistic, frictionless kind of world, once the weight had momentum it would keep moving until another force is put upon in, however with friction, the weight will eventually stop and to keep dragging it requires the continual application of force. All real fluids exhibit this same drag force, but in fluids we rename friction forces as viscous forces, and call the amount of internal friction (or resistance to shear), viscosity. Viscosity, like temperature and pressure, is an emergent property associated with a group of molecules and can’t really be ascribed to a single molecule – more a statistical property between them.

All real fluids, including liquids and gases, exhibit internal friction – with different levels of internal friction depending upon the fluid. We have an innate ability to distinguish this, at least with liquids, but we tend to use the term “thickness” to describe it. For example, everyone knows that honey is thicker than water because it doesn’t move or pour so well. Scientists call this thickness, resistance to flow, or internal friction: “viscosity“. In fact, the viscosity of liquids can be quantified and are often measured in an apparatus looking much like our galactic disk. A rod, with Ri is suspended in the liquid and is forced to turn at a constant rate. A second ring, with height H and diameter Ro, is attached to a spring. Due, once again, to molecular attraction, the molecules of the liquid nearest to the rod and outer ring move at the same speed, but the rod is turning/rotating while ring isn’t. The property, known as the “no slip” condition that exists between fluids and solids can almost universally applied in solving the differential equations that govern fluid mechanics (at low Reynolds number), but it needs to be emphasized that it exists for real fluids only. I would be remiss if I didn’t also admit that a little bit of heat is generated – that is the mechanical energy isn’t completely conserved due to the viscous drag effect.

If we consider the rotational movement from the rod outwards, the molecules nearest the rod turn at the same rate or period as the rod. This causes these molecules to move past, or shear past, the next layer of molecules further out. The intermolecular forces start these molecules moving, but they can’t keep up because the have a farther distance (2 x pi x r) to go around. While sped, up, the second layer shears against and speeds up the third layer, and so on, all the way to the outermost layer up against the outer ring. This outer ring is attached to a torsion spring and will only rotate a little bit until the force of the spring matches the viscous forces of the liquid on the outer ring. The amount of force on the spring, applied by the rotating rod is a measure of the viscosity of the liquid, and I am hoping that a you see that a very viscous (high drag) liquid such as molasses or honey would cause a greater force on the spring than say a much less viscous fluid such as water, which has a greater viscosity than a lubricating oil. One thing of note, is if we were to map out the shear planes or in 2-D shear lines, it would take on a spiral pattern running from the rod to the ring.

So the reason for my long-winded explanation of how a rotating viscometer measures viscosity was two fold. Firstly, it was to introduce you to the concept of viscosity. The second reason, is that our viscometer actually duplicates the spiral shear pattern (ie. spiral pattern) that exists within the galaxy. As we discussed previously, it is the balance of centrifugal force with gravity that keeps the gas particles orbiting the centre. The tangential velocity or angular momentum is always perpendicular to these forces so that both are conserved so that the orbits can continue indefinitely. Viscosity, however, now presents a new force that actually acts to diminish angular velocity along the plane or line of shear. As our frictional force slows down the molecules closest to the black hole – getting even closer without speeding up, there is a danger that our molecules will spiral closer and closer to the black hole and viscous effects slow it down. The black hole will fairly quickly swallow all of our gas, before a star can even form? What a catastrophe after all this work, just to end up with a fatter black hole! Fortunately, this sort of catastrophe will not happen on the scale of a galaxy, but will readily happen when hydrogen accumulates on a protostar.

To explain why viscosity doesn’t result in the black hole just gobbling up the gas, as it goes into a viscous, death spiral or friction, I will have to go a little deeper into the field of fluid mechanics, which I would hazard to guess is likely the largest field of research on the earth – as it is both complex and touches upon nearly every human endeavour. Now I have already introduced the concept of “viscosity”. Viscosity is indeed a quantifiable “collective” property of any fluid, that is actually fairly well predicted by modern thermodynamic equations of state, along with the relationship of pressure, density, and temperature – the other main collective properties. Perhaps the second most important calculation we can do is the Reynold’s number. Reynolds number, or “Re” is technically the ratio of the inertial forces that are taking place in a moving system (such as a galaxy) to the friction or viscous forces taking place. It really isn’t used directly in further calculation, but more like a litmus test is for acidity / alkalinity of water – except Re is a test of whether our flow regime and viscous system is well behaved, as we have described it so far, or whether the flow is chaotic and turbulent. Gentle breezes that you may feel outside will have a low Re, but gusts – the kind that you feel on an airplane flying through “turbulence” is caused by a high Reynolds number. Almost universally, an Re less than 1000, will mean nice, orderly flow or laminar, while Re numbers greater than 10,000 will mean “turbulence”. Whenever we look at a fluid mechanics problem we should look at what the viscosity is (which is just a property of the fluid), and then use this viscosity along with inertial forces of the dynamic system to determine whether our flow is turbulent. We can actually calculate what the Reynolds number is for a galaxy, but before I do, I want to demonstrate why viscosity and Re is important for a few devices we make.

Even the atmosphere (a gas!) around us has viscosity and exhibits a resistance to flow, that we typically refer to as “wind resistance”. One of the things we like to do with our atmosphere, other than breathe it, is to shoot golf balls through it. At first, we used smooth balls, but inevitably, due to the no-slip condition of the air molecules next to the golf ball and the viscous drag this had on the relatively still air that the golf ball passes through, this wind resistance limited how far we could hit the ball. As we continue to hit these golf balls around, we found that we could hit older (scuffed, dented, and chipped) golf balls farther then newer smooth ones. After applying our knowledge of fluid mechanics we found that if we could make the flow of air around the golf ball turbulent, the no-slip condition would be somewhat violated and this would reduce the actual wind resistance on the golf ball. That was what the imperfections on the older balls were doing – reducing the overall frictional drag on the golf ball. This transition of the golf ball from laminar to turbulent flow was so important that we now manufacture golf balls with pre-roughness as this lower the Re when turbulence onsets. Hopefully, I have also gotten you to realize that gases, and not just liquids have viscosity!

As a second example, more germane to our galaxy problem, is a centrifugal pump – a mainstay of our modern society and used to move liquids about just about everywhere. A centrifugal pump acts like our galaxy only in reverse – more like our viscometer example. Liquid’s are introduced via the centre of a mechanical impeller that spins to give the liquid angular momentum or centrifugal force that acts in direction directly away from the axis (centre) of the pump causing it to accelerate in this direction. The pump is configured in a disk shape to that the surface area available to flow increases with radius – geometrically causing the liquid to slow down, but the rotation of the impellers can keep adding centrifugal force that, instead of adding momentum to the liquid adds more valuable pressure instead. The pressurised liquid is then pushed into a pipe that lies tangential to the pump outer annulus. The spiral shape (much like the spiral shape of a galaxy), is used because the fall along the lines of shear – along the lines that we want the liquid to travel. If we used a straight armed, “paddle wheel” type configuration, a lot of the mechanical energy would not be placed in the direction we actually want the the liquid to flow in, and the pump would be much less efficient.

Unlike our golf ball, however, we are actually making use of the viscous drag to energize the liquid and it turns out that in the case of a pump, turbulence is definitely not to be desired. It is via the viscous drag of the impellers that energy is transferred from the impellers to the liquid and any reduction of viscous drag will reduce pump efficiency. As in the case of the golf ball, however, if turbulence (eddies and random currents) occurs the drag that is provided by laminar, well ordered flow will be reduced. If a pump is asked to perform its normal operating range of pressures (too low) and flow-rates (too high), turbulence will occur and the efficiency will be reduced. If the power to the pump in increased further still and asked to turn faster still, cavitation can occur. Cavitation ocurrs when pressure within turbulent eddies get so low that the liquid actually vapourizes causing the impellers to lose grip (viscous drag or friction) on the liquid. This loss of grip on the liquid, dramatically reduces the pump efficiency at moving water, and simply creates eddies in the water vapour. The reaction temporarity feeds on itself with almost all the turbulence transferred to to the low vapour portion of this now two phase (liquid and vapour/gas) system. When this occurs in the real world, the pump essentially loses all grip on the liquid in the pump and the motor can burn out because it just can’t get a grip on the low viscosity gas.

Cavitation in a water pump, occurs because of the ability of water to form into two distinct phases – low pressure, density, and viscosity vapour and higher pressure, density, and viscosity liquid when subjected to high turbulence and shear associated with a high Reynolds number. The capacity limit of a centrifugal pump via turbulence and cavitation can be determine by use of the Reynolds number – with the characteristic fluid velocities, properties and pump dimensions. As you recall, our Re number is the ratio of inertial to viscous forces and so speeding up the pump also increases the Reynolds number. At low Reynolds number the flow is termed laminar or regular and turning up the pump works fine. As the pump keeps spinning faster, the Re number will further increase and eventually the Reynolds number will exceed one to 10 thousand and indicate that turbulent eddies will form and cavitation will begin.

Now I think we have sufficient background to turn back to our galaxy problem, where we would like to know both the viscosity of our hydrogen molecular cloud and the Reynolds number of orbiting system – to determine if it is laminar and well behaved – or turbulent. For viscosity, we know that the temperature of a molecular cloud is very low, and in fact we don’t really have a problem in a lab getting to such cold temperatures. We also know that the gas pressure in a molecular cloud is also very low, and such low pressures in contrast, are very difficult to achieve. The lowest temperature/pressure measurement I have been seen made on molecular hydrogen is at a mear 14K and a pressure of 7.5 kPa (which happens to be the vapour pressure at 14K). The value reported happens to be 6.5E-7 Pa.s (National Institute of Standards and Technology). This value might not mean much to you, other than the fact that it is indeed a very low viscosity – even compared to other gases. I am not at all bothered that we cannot measure viscosity down to the pressures that would exist because, while viscosity of gases are a strong function of temperature, they are almost completely invariant to pressure. (This fact may at first be surprising, but ends up being a mainstay at simplifying the flow of compressible gases. I won’t bother you with the full explanation here though.) For our purposes, this does mean we are good to go with this viscosity assessment, knowing that at least in the realm of orders of magnitude, it won’t be wholly inaccurate.

This independence of gas (or liquid) viscosity on pressure is very important because it is a bit of “trick” that nature plays on us. Although we cannot directly measure the viscosity of hydrogen at extremely low pressures, we know that at pressures we can measure viscosity, it is independent of pressure. (As it turns out, this viscosity independent on pressure” is not just for hydrogen, it is the same for all gases.) At the same time, we can logically assert that this must break down as the molecules get farther and farther apart as pressure drops and the viscosity must decline as pressure and density approach zero. The problems turns out to be just like the Clampetts investigating what is causing the ring sound in their house. Every time they try and investigate where the sound is coming from, someone comes to the front door. Even if we could measure hydrogen viscosity at the very extreme low pressures we desire, every time we went to the low pressure the hydrogen would undergo a phase change – that from molecular (cloud) hydrogen to atomic (ISM) hydrogen.

This means that both statements can be true at the same time. The viscosity of diatomic hydrogen molecules is constant with pressure, but if the pressure is dropped to low it will undergo a phase change to atomic hydrogen, which does have a much lower viscosity than the molecular version. We discussed the thermodynamics/phase behavior of hydrogen in Parts 1 and 2 of this post series. I hope that you can see where this discussion is going if we try and relate cavitation in a pump with “galactic” cavitation. Just like a more viscous liquid such as water can cavitate to a less viscous vapour in a pump, it posited here that a more viscous hydrogen molecular cloud (MC) will cavitate to a less viscous, atomic interstellar medium (ISM) in a galaxy. If you think I am setting the stage here, you would be guessing correctly – but lets not get ahead of ourselves.

The next step involves calculating the Reynolds number, for which a bit of guessing is required, particularly about molecular cloud density in a galaxy. Remember – we don’t want the average density of ISM and molecular cloud, but the density of the molecular cloud itself which, according to my astrophysics textbook is typically 50,000 x that of the ISM (ref “Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 1989, Academic Press, Inc.) that I have used the molar version of an ISM density 100 molecules/cm3. I have use the orbital period and distance of the sun in the Milky Way for my calculation, taking these “Milky Way” parameters as representative of a spiral galaxy. While these assumptions may seem very imprecise, they are accurate enough to calculate a Reynolds numbers, of which only the order of magnitude (the part that comes after the E) is important.

The resulting Reynolds number we calculate is 1.5E24, which is extremely high. It tells us that the viscous forces are simply overwhelmed by the scale and rate of rotation around a galaxy and turbulence and cavitation can occur in our galaxy. While the Reynolds number of a galaxy depends at what radius it is calculated, it is sufficient high to be safe to say that this state of turbulence will exist regardless of the radius tested. It is also fairly safe to say that this “ability to cavitate” condition will also exist for any galactic disc reasonably comparable in size to the Milky Way and even much smaller galaxies. If we imagine the galaxy as initially consisting of tightly wound laminations of gas orbiting the central black hole, then cavitation can be thought to occur along generally. but not necessarily, two lines of shear around the galaxy. The galaxy will, in essence, delaminate in the form of spiral arms curving out from the donut hole to the outer edge of our torus.

The delamination of the galactic torus by “delamination” causes the torus to expand and become much larger than if it were a simple disc. Not only do the resulting arms have to accommodate the hydrogen material itself, but also the space in between them must contain something. This begs the question of what is in the arms?, and what is in the space between them? If we turn our attention to our images, we can see that there must be a difference, because the dust lanes, emission areas, and the highest density of stars are all seen in the spiral arms – as we can see in this face-on mapping of our Milky Way galaxy. While these observations are true, you will recall that we haven’t even put stars and dust into our galaxy model yet.

For our model presented here, there is only hydrogen around a black hole. Astrophysicists have tried to determine if there is any difference in the 21 cm IR emission from the electron spin flip that can occur in hydrogen atoms, and the short answer is that other than a debatable different in atomic density made fuzzy by the blocking nature of dust, there is no difference between the hydrogen in the galactic arms or spirals, than there is in the space between them. This conclusion from the observations is not true, and we have to circle back to our original assumptions regarding the composition of galaxy as an “ideal” monatomic hydrogen cloud as a single phase fluid without viscosity. The real conclusions are much more complex, dynamic, and beautiful than our oversimplified assumptions allow.

Just like the cavitation of water into two separate phase, two separate phase/states of hydrogen are formed in the delamination of the galactic arms, or rather the creation of galactic spirals that have already been introduced to you. One state, molecular diatomic hydrogen associated with higher pressure, density, and viscosity occupies the spiral arms (98% of the mass), while another phase, monatomic hydrogen, associated with lower pressure, density and viscosity, occupies the space (98% of the volume) in between the arms. The galactic system puts as much of the turbulent, energy dissipating behavior into the monatomic phase where the low viscosity offers the least friction or drag, just as our cavitating pump puts almost all of the turbulence in the low viscosity water vapour. The resultant eddies in the monatomic ISM seem to form a container that confines the spiral arm molecular clouds to their lanes. This picture itself is oversimplified but sufficient for now, but the real picture is much more dynamic with monatomic hydrogen becoming diatomic (molecular) hydrogen and vice versa at the interface between spiral arm and spiral gaps.

One of pitfalls of a single monatomic hydrogen gas general assumption has led to an simple accounting error regarding the mass of hydrogen itself or, in other words, led to the error that hydrogen molecules have not been property counted. This is despite the most sophisticated algorithms meant to correct for dust hiding the 21 cm monatomic hydrogen spectral line. Hydrogen, in its molecular form has its two electrons spinning in quantum superposition – meaning that hydrogen spin flips will not occur. Molecular hydrogen does not emit 21 cm IR and is invisible. In other words, one cannot count what one cannot see. (I will elaborate more on this in Part 4). Consequently, the phase difference between the spiral arms and the spiral gaps is missed by astrophysical observations alone.

The high Reynolds number, combined with the ability of hydrogen to form two phases, means that any attempt at forming a hydrogen cloud in a homogeneous orbiting disk would be met with immediate cavitation of the cloud, due to the onset of extreme turbulence. The rotating disk of cloud would immediately form eddies along spirals of shear that occur during laminar rotation (ie cloud windings). In the example of pump cavitation, the more viscous liquid “cavitated” to a much less viscous vapour or gas via a thermodynamic phase change. In the case our molecular cloud, the more viscous hydrogen MC partly cavitates to its much less viscous atomic ISM. The creation of ultra low density ISM requires much more space than the MC and the size of the galaxy will increase rapidly as the molecular arms move apart. In an effort to reduce energy dissipation, almost all of the fluid shearing activity will move from the molecular cloud portion of the galaxy, to the much less viscous, ISM portion – leaving two molecular spirals to contain most of the galactic mass. It would certainly be a site to be hold, with the best analogy would be the blooming of a flower, only our hydrogen is invisible even cavitation were to suddenly occur.

The extremely high Reynolds number and hydrogens ability to form two phase states (atomic ISM and molecular clouds) means that any attempt at forming a hydrogen homogeneous orbiting disk on a galactic scale would be met with immediate cavitation of the cloud, due to the onset of extreme turbulence. Now I am not saying that this cavitation process would actually occur – more like the molecular clouds, when forming a disk around a block hole, would naturally form spiral arms, leaving a gap of ISM between them to adsorb, in a low dissapatory way, all the eddies and turbulence that is going on. The rotating disk would immediately form eddies along spirals of shear, that maintains as much higher pressure withing the relatively tranquil molecular clouds. Much as a cavitating water pump puts its turbulence in the low viscosity, low pressure vapour phase, leaving the liquid water clinging and rotating alone with the pump impellers.

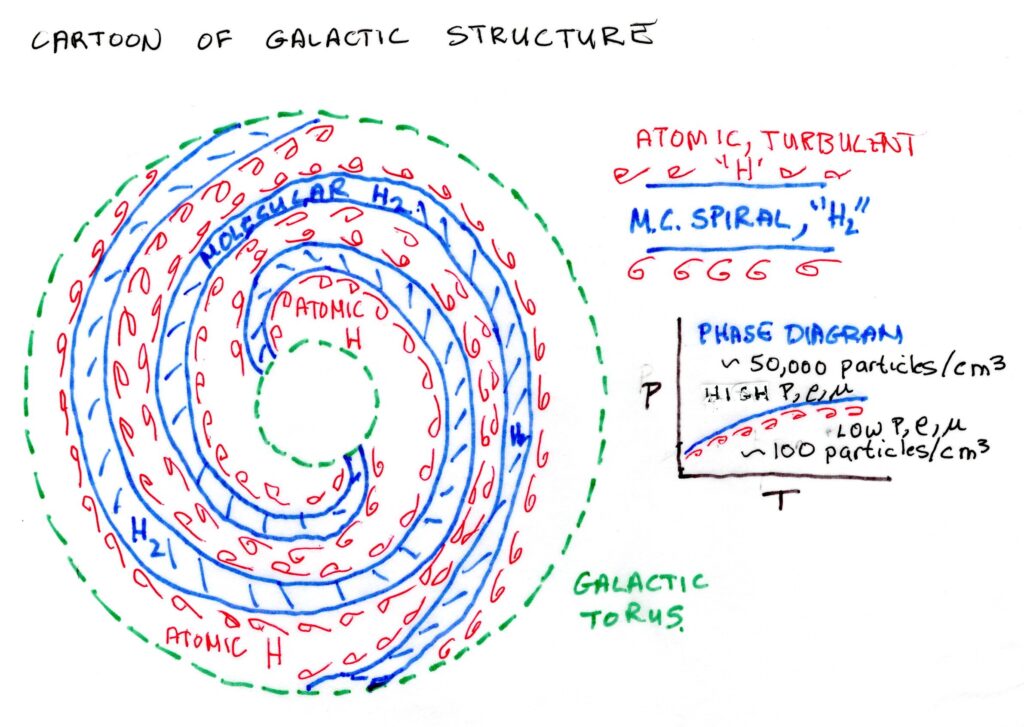

In this cartoon of the spiral structure, you can see that the spiral “arms” are contained by the turbulence of the atomic ISM (via Bernoulli forces) The galactic torus/disc is contains both the ISM and MC between its outer and inner radii. It is only a cartoon, however, and we need to bear in mind that in reality – 98% of the volume of a galaxy is taken up by the ISM, while 99% of the mass is due to the hydrogen molecular cloud phase and its star-children.

Alas we have spiral arms! Typically, two spirals of cavitation would result, running right through the galactic centre, so as to provide gravitational symmetry and prevent galactic wobble (but more of this in Part 4). The spiral arms are induced and confined by the eddies coupled with their own gravitational pull. As we will find out, the system forms a stable, semi-steady state but it is still dynamic and moving.

Most peoples’ vision of a chaotic system, is of one without order. But, order does arise out of chaos. In our spiral galaxy, most of the violent shearing turbulence exists within galaxy is confined to the ISM in between the molecular cloud spirals. The spirals themselves bend around each other, keeping thier distance. As we shall see, the arms themselves still need to balance their centrifugal force with gravity, but gravity now must also counter the lateral viscous forces that want to continually wind the arms (the winding problem). The galaxy also configures itself in a manner that it almost turns with a constant period (like a CD, record, or arms on a clock). As we shall see the configuration of the spiral arms, with own internal gravitational forces superposed with the rest of the galaxy provides an answer to both the winding problem, and the galaxy’s ability to be stable under substantial perturbations. Hopefully, you will stay tuned to this website for Part 4 of this series, which is all but written – just in my head for now. This will address both the “winding” problem and the “constant period” problems that makes use of the gravitational field of our newly explained spiral molecular cloud arms.

Some Cleanup

It has continually disappointed me that our popular explanations for the spiral nature of galaxies has failed so terribly to address what is so obvious to scientists with a thermodynamic and fluid mechanical background. I have tried to address this with two examples, with the centrifugal pump and golf balls (which I will refer to again in the future, once we introduce stars). But more and more examples lie all around us in turbulent spirals, in the form of centrifugal compressors, vortex phase separators, aeronautics (eddies off of wings, and the stalling of aircraft, hurricanes and tornadoes, whirlpools, and even the draining of the kitchen sink. Even Richard Feynman stated that “turbulence is the most important unsolved problem of classical physics” and that he had two questions for God: “Why Quantum Mechanics?” and “Why Turbulence”. Yet all of this knowledge that we do have is disregarded when it is assumed that gases are all “ideal gases” (ie inviscid) by the arm-wavy argument that the molecules are far apart. This has relegated the study of galaxies to little more than a mere “categorization” exercise, with little true understanding of why these categories of galaxies exist.

The current state of understanding of galaxies is presented as the “Density Wave Theory“. It separates the gravity of the stars, separate from the gravity of the spiral arms to explain standing waves of density / pressure via something called a “traffic jam”. The density wave theory is admirable, in a way, as it comes from the realization that hydrogen must exist is two states – each creating a gravitational field that interferes with one another to create the spiral arms. But this puts astronomy is in a corner here – we know that two states of hydrogen must exist to create the spiral arms, yet astrophysicists say that it cannot discern any material difference in the hydrogen between the regions within, and between the spiral arms – clinging to the no-viscosity, monatomic, monophasic assumption about hydrogen. Since, the astrophysicists cannot see any difference, the conclusion is made that there is no material difference. There only way out of this problem is to assume that the spiral arms are somehow created with interference with stars. The stars are then used as the second phase of hydrogen to create spiral arms. But this begs the question, the amount of stars in the galaxy is dynamic too (in the beginning, there aren’t any) and the density waver theory presents no reconciliation of this. It also place a very long timeline on the creation of galaxies that simply does not fit with the observations of early galaxies made by JWST.

Rather than come up with a way out of this predicament – I have chosen here to re-examine and challenge the fundamental assumption made by most cosmologists and astrophysicists – that the hydrogen in a galaxy behaves like an ideal gas. Astronomers themselves, are seeing viscous or friction effects themselves – most recently in their explanation for the heating of the accretion disk around a black hole, so I am hoping that with time, astrophysicists and cosmologists incorporate fluid mechanics and thermodynamics into their descriptive tool kits.

As long as astrophysicists and cosmologists fail to listen to other scientific disciplines and cling to their individualistic , many body approach to modellling they will be thwarted in their understanding. Some, rather than facing the truth, have even resorted to proclaiming that an ideal gas does indeed have viscosity. Please don’t believe it! What these articles are describing is dispersion, not viscosity. They heavily lean on a no-slip condition for their explanation which, by definition, cannot hold for an ideal gas. Furthermore, if an ideal gas did have viscosity, then what is it? Of course, the answer is it cannot be quantified because it isn’t real. Measurements also show that dynamic viscosity is different for different gases – how can this be? In many cases, fluids can indeed assumed to behave in an inviscid manner (viscosity = 0, i.e. an ideal gas or superfluid), and this allows for the simplification of the difficult to solve “Navier Stokes” partial differential equation to the “Bernoulli” ordinary differential equation for steady state inviscid flow. This may be why fluid mechanics is not included in many body style outer space simulators – they are the wrong type of simulator and what is needed is a finite difference simulator – a completely different formulation – for these PDE’s (partial differential equations). The flow of real viscous, compressible gases has been tackled in many technical fields employing numerical simulations – for all practical purposes compressible gases can be treated as incompressible liquids through use of pseudopressure and there is no reason why astophysics can make use of a solution from a different technical specialty.

A final key to understanding the gravity field and solving the “winding problem” in a spiral galaxy means abandoning the “Shell Theory” for disc, toroidal, or spiral structures. This is an argument that has been placed to me. The fact is the the encompassing shape of a galaxy is a torus and if one looks at the derivation of the Shell Theory, one will find that it is only applicable in spherical cloud. However, even in a toroidal galaxy, a complete description of the galaxy must explain why the galactic arms don’t wind upon themselves as the galaxy turns, at least more than a simple “because turbulence prevents it”.

Hopefully, I have garnered some interest, but I will be turning to mechanical engineering, dynamics, and strange gravitational behavior for this explanation in Part 4 of this series.