As my first topic on my website, I wanted to tackle a subject that I believe hasn’t been given due attention elsewhere – why are there spiral galaxies and why do so many galaxies present themselves as spirals?

To form a galaxy requires two physical ingredients – the first of which is a bunch of hydrogen atoms. As far as astrophotography is concerned, hydrogen in gaseous, not excited form is transparent and colourless, and the only way we can see the hydrogen in a galaxy is either in the form of a star, or when it is in an excited state (Halpha or Hbeta emissions). Most of the hydrogen in a spiral galaxy is neither, because as we shall see, a galaxy whose mass is predominantly stars, will cease to have a spiral structure. So this is worth bearing in mind, as most of the mass of the galaxy is our first ingredient…invisible hydrogen.

Before we get too far, I have to talk about a couple of properties of our hydrogen at the prevailing conditions of space. First off, the conditions (ultra-low pressures and temperatures) in space cannot easily be replicated in a lab, so we have to surmise what we can from the properties that we can measure together with analogies to how other gases behave. Fundamentally, in most of space hydrogen exists as individual atoms or ions- a proton and an electron that may be associated with one another. This basic state I will refer to as interstellar medium or ISM. The pressure and density is soooo low, that for our current purposes, you can think of this as a vacuum (at least for now).

It may happen, due to some gravitational force, that if this ISM is compressed from its ultra-extremely low pressure to one that is merely extremely low (by our standards), hydrogen atoms might encounter each other with enough frequency and force that they will form H2 molecules and transform into what we will call a molecular cloud. Since the pressure is now higher, this gas is much more dense and its properties become very different from ISM.

As it turns out, the galactic arms in a spiral galaxy are made (primarily) out of this, somewhat compressed, molecular cloud (MC), separated by lower pressure atomic ISM. While both the MC and ISM are invisible in our image, we only know this from our images via the many products of hydrogen behavior (stars, dust, and narrowband emissions) created within the galaxy itself.

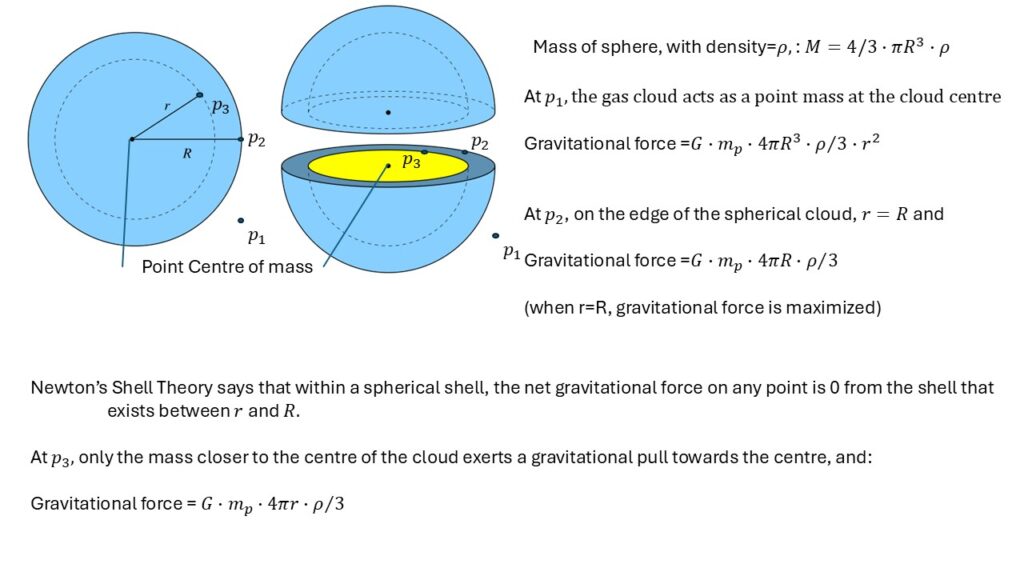

It is popular belief that a sufficiently large MC alone can create either a star or even a galaxy, and this misconception is propagated using Newton’s Shell Theorem (math below)…

The Shell Theory suggests that to any point at the outer edge of a spherical shell or cloud of material or farther away (points 1 and 2), the object will act as a point source gravitational attractor with a mass equal to that of the entire sphere or cloud. What is really cool, is that for any point within the cloud (point 3), the centre continue to behave as a point gravitational attractor, but with a reduced mass comprised of only the matter that exists closer to the central point. Perhaps the most important point of the theorem is that the material that exists outside of the sphere defined the distance from the central point to point3 exerts no net gravitational influence within it. It is as if (gravitationally at least) that it doesn’t even exist as far as point 3 is concerned.

As we will see in future parts of this galactic blog series, Shell Theory is very useful in describing the spiral structure of galaxies in terms the distribution of the molecular cloud. Even if you don’t understand the math, the important point is that the gravity of the material further out from the galactic centre has no influence on the structure of the galaxy closer to the centre – even if it is gas or stars or dust (that I haven’t even mentioned yet). While everything in the middle pulls the MC towards the centre, material further out does not pull the galaxy apart – so long as the galaxy is spherically symmetric.

Unfortunately, this theorem has been used a bit like vodoo by some cosmologists and astrophysicists in that it has been relied upon to describe some phenomena that it just doesn’t work for alone. Examples are the creation of stars, black holes, and the universal tapestry.

But here is where it all falls apart for the following reasons.

- The theory goes that that the gravitational pull of the “central attractor” will increase as we add material (gasses) on the outer edge (making the sphere more massive). Eventually, a critical cloud diameter will be reached where the cloud does collapse, due to this gravitational pull and the gas will condense to the centre (and form a star!). However, this is disproved by the theory itself, in that any material added to the outside of the sphere cannot change or influence what is in the inside – and therefore, the inside of the sphere cannot collapse. The gravitational pull at the real centre of the cloud will be zero, no matter how much material is piled on the outside

- The equations shown have assumed a constant density, more reflective of a liquid or solid, than a gas. If one could create a spherical gas cloud, its pressure and density would be greatest at the outside of the cloud and almost nil in the middle. The density of gas in the sphere would adjust (according to isothermal conditions) such that outward pressure would counterbalance the gravitational force at all arbitrary radii. The centre of the cloud, would indeed have no gravitational forces, but also, no pressure or density. At the same time, additional material added to the outside of the cloud, would have to be added at increasing pressure, requiring work be done on the material outside of the cloud. To penetrate the outside shell and create a collapse, gas at a higher pressure would have to be added.

- Adding material to the outer edge would require some magic to stop it at precisely this radius. Material will accelerate towards the sphere, pass right through the edge past the middle of the cloud and out the other side. Gravitation is not dissipative of the energy. It will simply trade off potential with kinetic energy 1:1 as it passes through.

- To contain any gas cloud from the outside will require a shell of condensed material that can exhibit an opposing pressure against the cloud to keep it contained. In other words, the only way to contain the gas at the outside of the sphere would be a balloon (or pressure tank).

To summarize, while Shell Theory is quite interesting and certainly applicable to condensed materials, it cannot and does not apply to gases. Gases, by definition will always expand to fill their container – they will not be confined by an outer shell of high gravity, rather because pressure will defy containment at the spherical centre.

I don’t want to belabour the point here, but the concept of critical cloud radius, or Jeans instability (or more accurately, Jeans swindle) is one of those concepts that really should be laid to rest and given a decent burial. In fact, the only way to keep a molecular cloud contained is via a concentration of condensed matter at the cloud centre. Nonetheless, we will make use of the Shell Theory when describing the balancing off of forces – and why it only holds for spherical geometry.

While Shell Theory cannot contain a gas cloud from the outside, a sufficiently large condensed point mass can contain the gas cloud from within. If we were to carefully place such a point mass right in the centre of our spherical cloud, without inducing any orbiting or angular momentum, the cloud can remain spherical. However, now the cloud will have the lowest potential energy right at the point mass, and not at it’s outer shell. The pressure / density would be highest at this new centre, with gas molecules held tightest against the point mass, where the potential energy becomes a minimum. The size of an individual gas cloud that can be contained by such a point mass is dependent upon the diameter/mass of the point condensed mass such that the derivative of pressure with respect to radius is always negative.

This brings us to the second ingredient for our galaxy, and that is a point mass strong enough to hold all the gas together. As a pick of something small, but heavy enough, I would choose either a black hole or a neutron star – maybe even a very massive star? for a very small cloud. To give a sense of what I am talking about, we need it to be large so that when approaching our cloud, both the cloud and the mass can become gravitationally locked together. In the case of our Milky Way, the mass of the Sagittarius “A” black hole that forms our galactic gravitation attractor is very heavy (4.3E6 solar masses), but only 0.3% the mass of the whole galaxy (1.5E9 solar masses). Even with such a relatively small central attractor, the Shell model for our galaxy can be made stable.

In the end, the gravitational fields of both the “point mass” and the hydrogen particles (Shell model) will be superposed. To analyse the galactic structure, we can still make use of Newton’s Shell Theory, we just have to add the gravitational force of the central mass to that of the cloud. Ultimately, a point source at the galactic centre is what holds the MC together as a galaxy.

The solar system is full of examples where a central mass holds on to a gas cloud. On Earth, the mass of the planet contains our atmosphere. In Earth’s case, the highest pressure exists at the surface, and not at the outer edge as in our Newton’s shell. On Jupiter condensed material is sufficient to make its hydrogen and helium super-critical at its core. Even our sun, made out of liquid metallic hydrogen, has a gasous (or plasma) atmosphere. These examples hold on very tightly to their atmospheres, but in a galaxy, the gases are not such much an atmosphere on the mass, but more spread out – despite the centre actually being a black hole!

Nasa image

One final note, here that I do wish to point out, is that I did specify that the point mass had to be placed very carefully at the centre of the gas cloud so as to avoid any angular momentum between the gas molecules and the central gravitational attractor. In practice, this never occurs, and there is always some angular momentum of the gas cloud. So, while I may have misled you into believing that there can be a spherical galactic gas cloud, I have yet to image one. Instead, I turned to AI to generate what such a cloud might look like. Please let me know if you happen to image something like this, because I might have to update this post.

To understand why this is, in my next blog, I will introduce angular momentum (centrifugal force) and how this balances off the gravity to create a dynamic, but relatively stable galaxy. Angular momentum will transform our cloud into a more recognizable disc shape. In addition, the non-spherically-symmetric disc shape will force us to partially abandon Shell Theory too. It may not seem very gratifying to end up with a spherical cloud with a black hole or neutron star in the middle – looking nothing like a spiral galaxy yet, but things are about to get interesting….